The valley of the Damodar River is a place of grief. India needed coal to fuel her dreams of modernity, and so coal was extracted from the flesh of the land here. No one asked the hills, rivers or forests. No one asked the Santals, the Mundas, the Hos or the Oraons, who lived on this land if their worlds could be destroyed so that our world could develop. The Damodar in flood was once a powerful force, free and blustering, smashing through all obstacles in its path. Fifty years ago, people came to spend their holidays nearby, in a land that was still lush with greenery, with clear waters and air that was still pure. But already disturbing images had started to appear, of entire villages deserted, clouded by smoke that came billowing up from the earth, where coal beds were burning night and day. Today, the sky is always ashen, the land is mostly as barren and lifeless as on an asteroid. Coal litters the land where it has been torn open down to the seams. Foul run-off collects in poisonous pools. There are places where you can look right into the heart of the fire raging below.

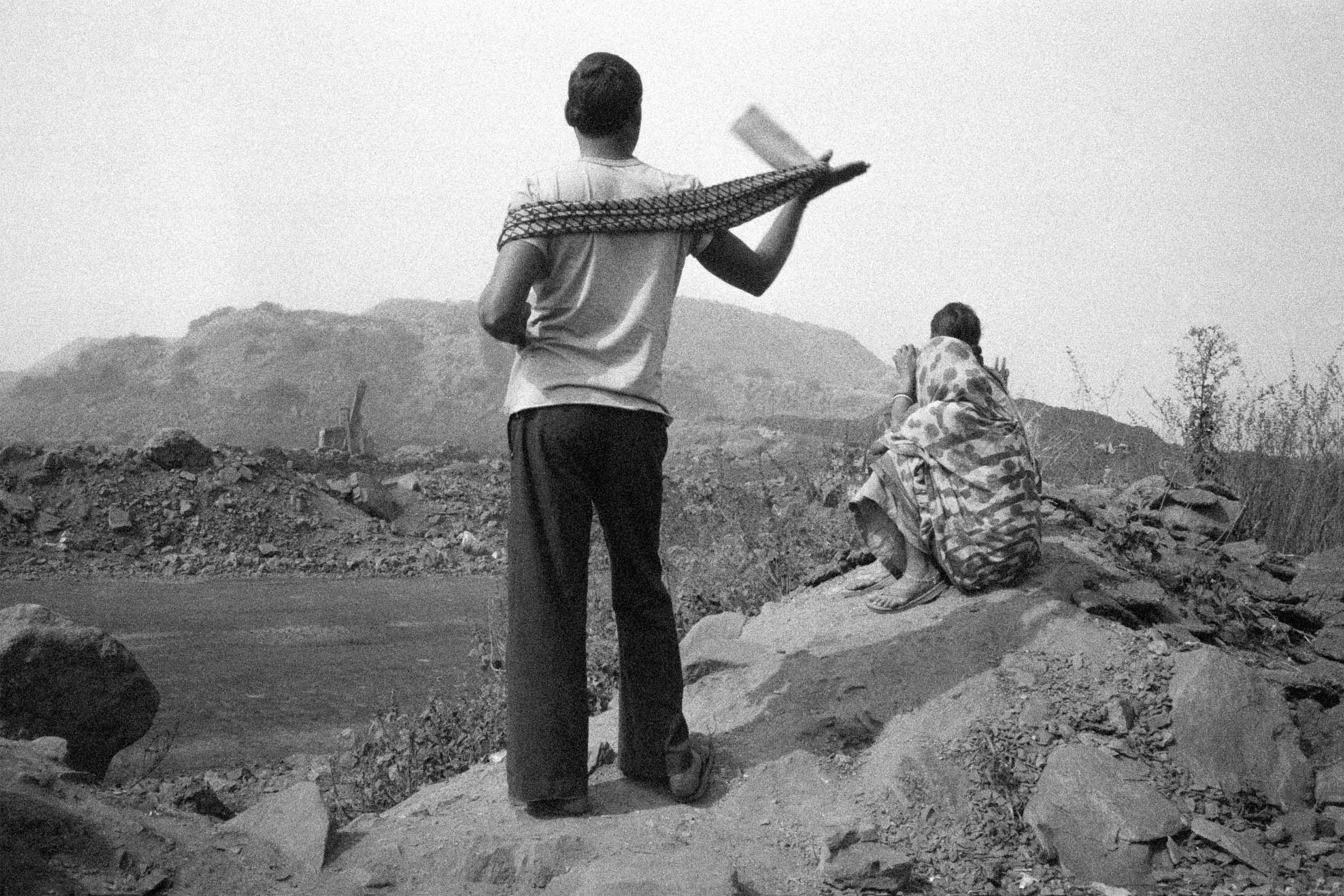

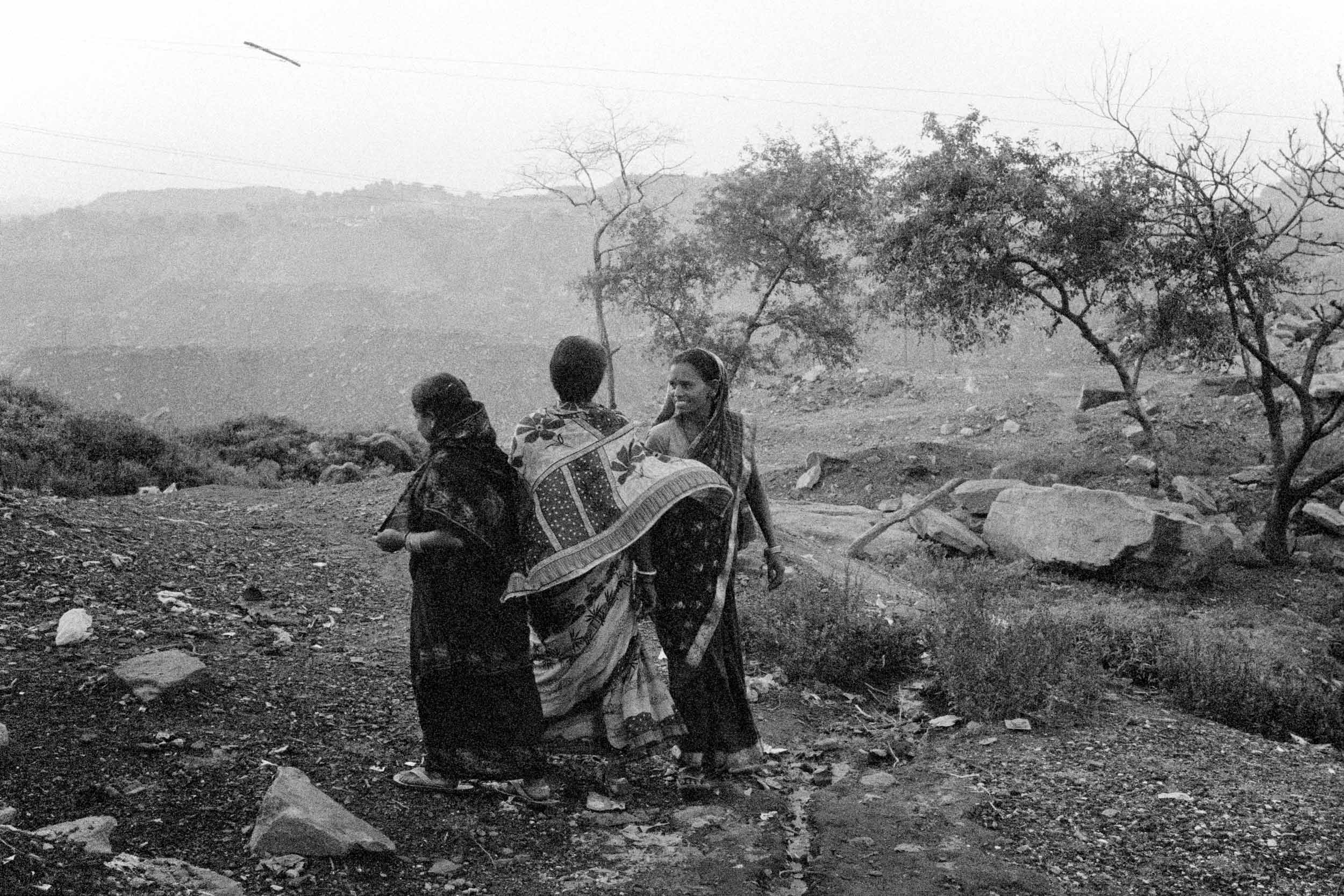

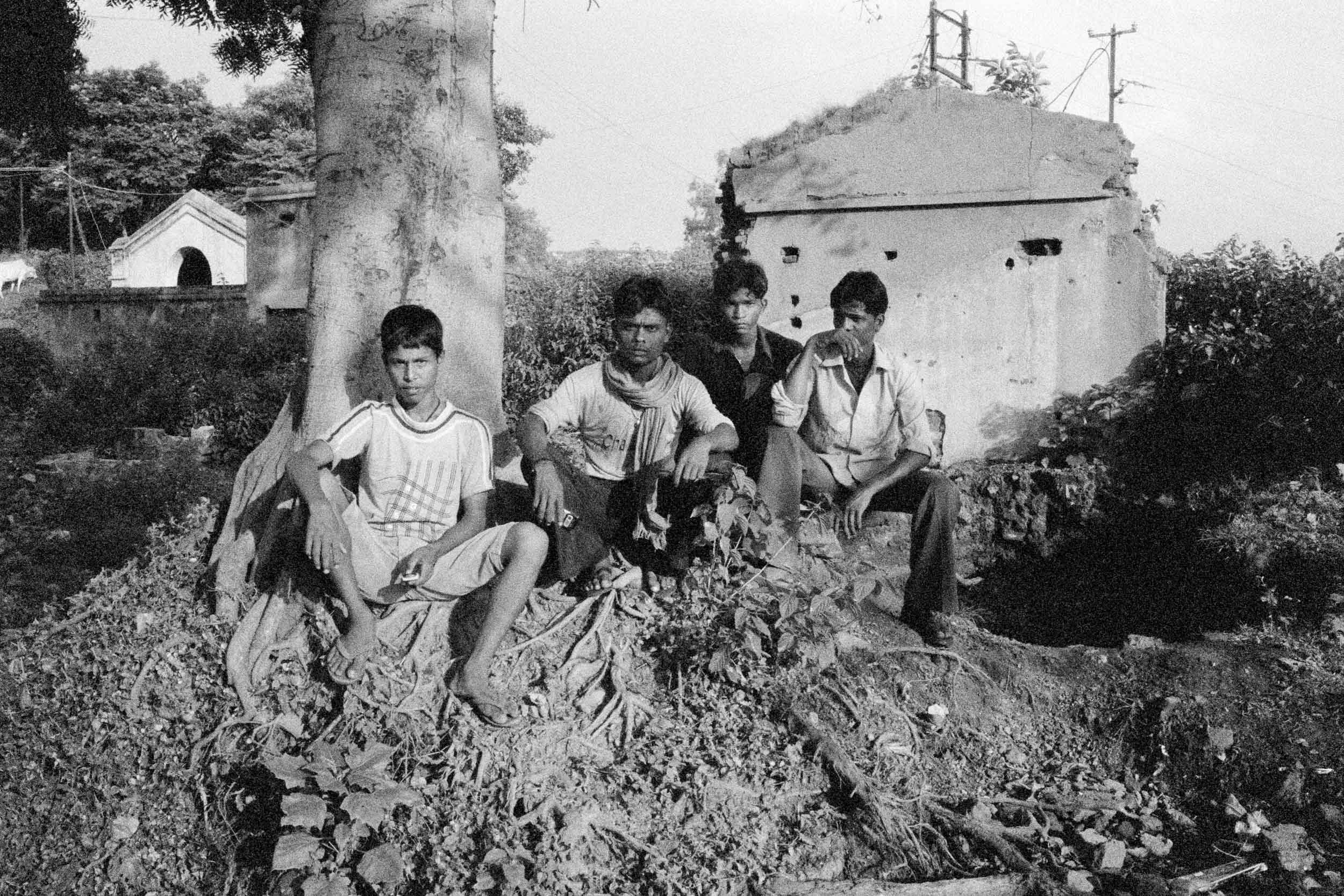

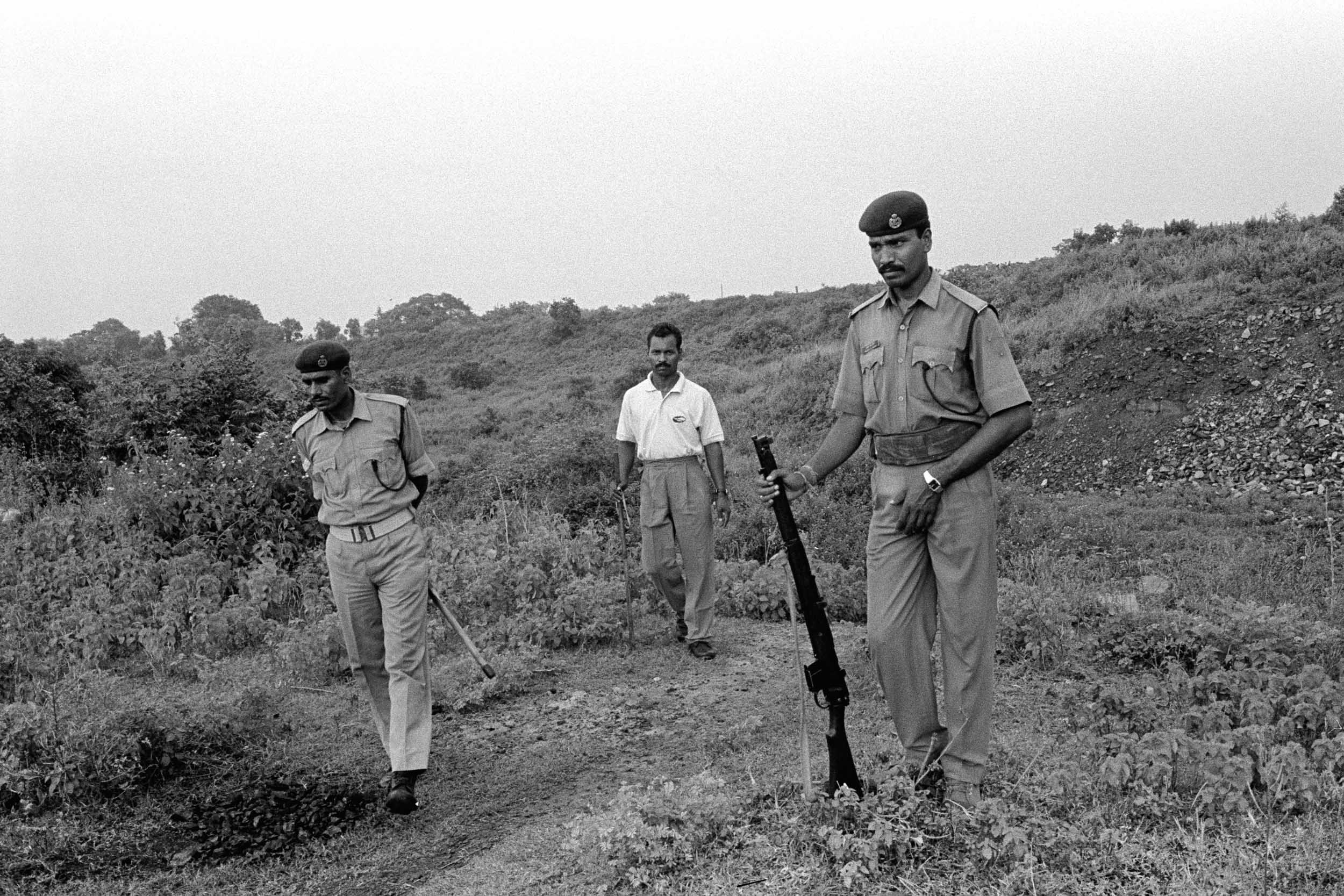

Those people that were not destroyed by the tragedy made it a part of their everyday lives. They dig the forbidden coal on the hillsides. They carry unbelievable loads on their heads or on two wheels, and take them to market. When a group of women in their bright clothes scatter across a coal face looking for a day’s pickings, they look like flowers against the black hillside. Housewives walk long distances to bring home drinking water. Neighbours gossip among the houses they hold on to in ruined villages. Children play improvised games of cricket on barren patches of earth.

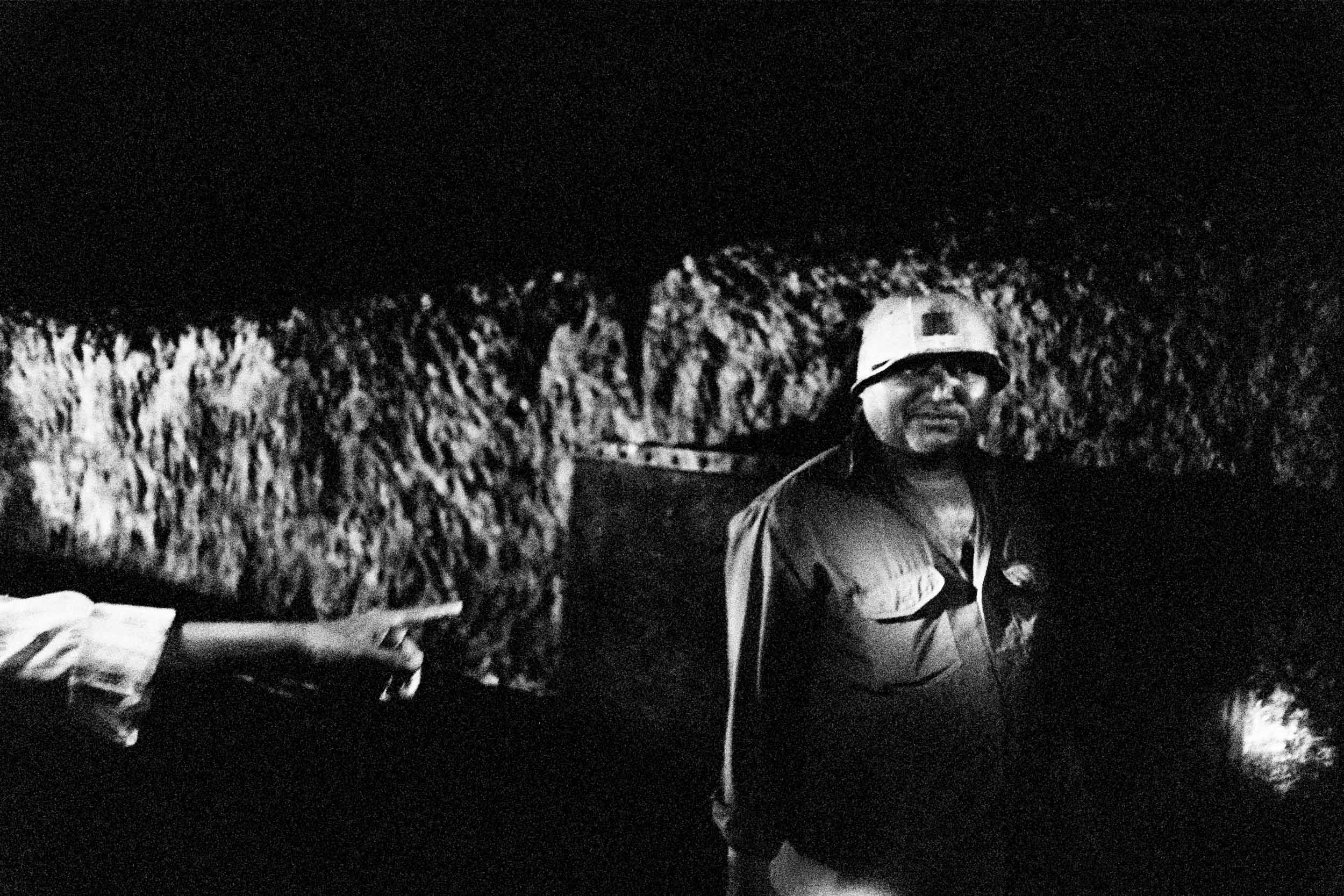

Fire is the dominant element here. It brings with it its own darkness. Everything around appears post-apocalyptic. Mundane acts and events appear metamorphosed, as if they are happening after a cataclysm.

Railway lines look abandoned, roads seem to go nowhere, and houses are in ruins. A bright yellow dumper surrounded in smoke looks like the survivor of a deadly aerial attack. A woman walking between two smoking hillocks seems set on a doomed errand; two women sort what is central to life here, and it looks as if they are searching for their fates in some mysterious vessel.

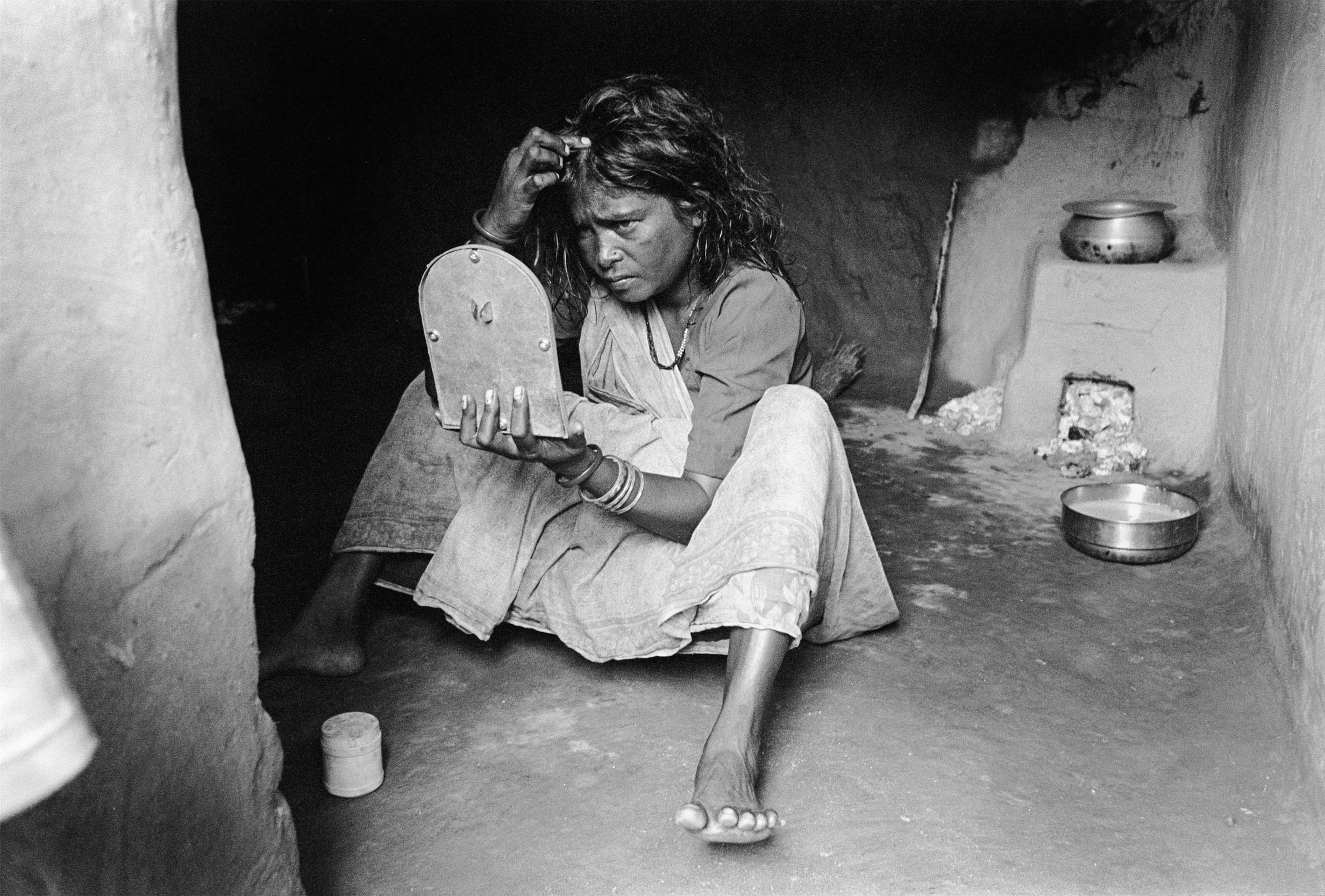

But people cling to their small dignities and pleasures. A man in a carefully laundered white shirt lights his smoke. A young girl looks radiant in her new dress in the courtyard of her home. Women groom each other and rejoice in their finery on a black hillside.

Tisra, Jharia, Katras, Dhanbad, these towns in the valley of the Damodar will keep supporting the nation’s fossil-fuel habit. The damage to the land is irreversible. We may only study the lives of those who are tied forever to coal and its tragic landscape. Their landscape will not change. They need to do this work to live.

- Aditi Nath Sarkar

Flowers Gallery London: Artist of the Day, a platform for artists since 1983. This two week exhibition showcases the work of ten artists chosen by established professional practitioners who have each nominated a talent of their choice.

The work on coal mining was chosen for the 2011 edition of the Artist of the Day. Nominated by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye.